I CAN’T REMEMBER THE first time I heard the slogan “No Voice is Louder than the Voice of the Intifada”. I was born at the peak of the 1988 Intifada, when this slogan first appeared.

I became aware of it during the second uprising, when the slogan re-emerged at the start of the millennium. When I chose the topic of my dissertation – the impact of a prevalent ideology in determining the options of sociological research in Palestinian universities – I found that the slogan summarised how the existing national ideology works against critical visions in social sciences and tries to silence them.

In my research I found that the slogan was a modification to one that existed during times of tyranny in Arab countries in the past century – “No Voice is Louder than the Voice of the Battle”.

Ever since I was born, I’ve been living through the “battle” in which no other voice should prevail. This is what happens when you live in a conflict that has not been resolved for more than 70 years. I live in Ramallah in the West Bank, an area that is subject to Israeli military occupation, according to the UN, since 1967. During this time there have been national movements working towards ending the occupation, but these have transformed into an authority that has signed a peace agreement with Israel that hasn’t led to peace.

Instead, understandings were reached that resulted in administrative and security co-ordination. At various times, this has led to periods of calm, with economic opportunities and cultural activity which were supported internationally. It seemed as if the battle’s voice had receded or faded away. Yet the administration maintained the battle discourse, which seemingly must remain above all others.

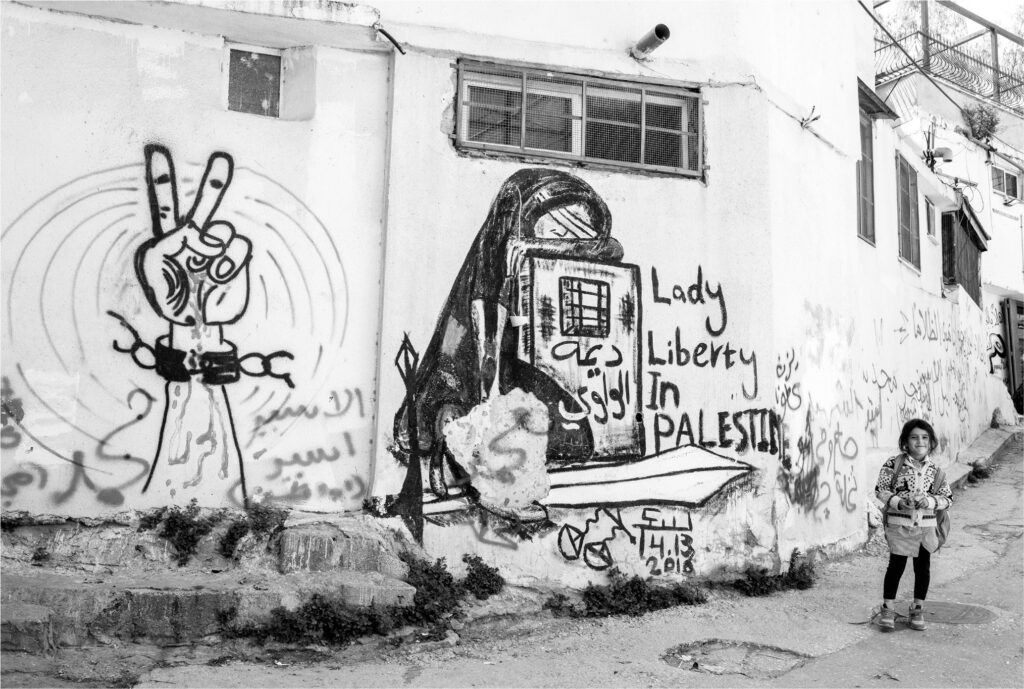

Years ago, on the wall of an oil press in the village of my maternal grandparents, I read a slogan that shocked me: “You are either a mine that explodes under the feet of the enemy or you shut up.” Underneath was the signature of a leftist faction. Reading this slogan, I realised that I was before two choices; I am either dead – because I am a mine that explodes under the enemy’s feet – or I am muted.

In 2016, when I wrote my novel A Crime in Ramallah, I was subjected to a dual-pronged attack.

The first was a legal attack by the public prosecutor and the Palestinian Authority, who confiscated my novel from bookstores and libraries, issued an arrest warrant against me and detained the book distributor. The second attack was on social media, which fed on the prevalent ideology and its logic.

This incident highlighted the reality relating to freedom of speech in the areas controlled by the authority. Accusations were hurled at me about public morals and the current law, along with charges I had committed treason and insulted national symbols that are prevalent in the discourse of the “battle”.

The current laws in force in the PA areas have remained a topic of legal argument. These include the penal code of 1960, which is a regressive law that restricts freedom of expression and speech as well as political freedoms, freedom of sexual orientation and the freedom of women. Furthermore, the law is vague and can be maliciously misinterpreted. The arrest warrant was issued against me on this basis. Efforts to amend the law or enact a contemporary law that allows for even minimal freedom of expression have all failed.

Instead, an electronic crimes law was issued in 2018. This further restricted freedom of the press and online expression. It included harsh penalties that had an impact on writers, journalists, artists and people who have now become hesitant to criticise the authorities even with a post or tweet on social media. Dozens of websites were blocked under that law, including a website whose editorial team I supervise.

Recently, major social media outlets have started censoring Palestinian content at an unprecedented level. As a result, I cannot write anything about the occupation and its practices in Arabic without the threat of my account being restricted or removed. Due to the weak algorithms of these sites in Arabic, the context is irrelevant – simply mentioning certain words is enough.

In an attempt that seems creative, social media users have begun to bypass the algorithms to avoid censorship by inserting symbols into words they think mean their accounts are restricted. Recently, this has evolved into a web application which removes the dots that are an integral part of Arabic letters, so that the AI machine cannot detect the words formed by them. This is interesting, bearing in mind that Arabic letters were originally dot-less 13 centuries ago. For a moment, everyone was happy with the ability to resist restrictions. However, I viewed this as a sort of normalisation with censorship, and I expected – along with many others – that these actions would succeed only as a form of protest. Clarity and freedom of expression are threatened because using such blurry letters hinders the communication process, which lies at the core of an open world and at the heart of these platforms.

This reminded me of writers, novelists and artists resorting to symbols to express what they want, using a sort of encrypted language. For example, they remove explicit statements in their stories and instead revert to a complex language that spares them the wrath of the censors.

It has become the norm to use symbolic language to talk about sex, cursing, politics and religion. Writers seem willing to sacrifice communication with the reader due to the fear of censorship. Actually, it seems to me that censorship has been internalised, evolving into deep-seated self-censorship, hence extensive symbolism in various genres, even in journalistic writing, is only expressive of an Arab censorship crisis.

Many thought that abandoning some words in my novel would have allowed it to escape the persecuting censorship, both officially and among the public. However, I believe that those words were a fundamental part of my style. I am also convinced that compromising on a few words means abandoning the basic right to write, and that whoever compromises on a word may compromise on an idea and then on an entire book.

Today, if I remain true to my conviction in regards to accuracy, clarity and freedom while writing on social media (which became a part of the “battle” through which I have lived my entire life) then I face two choices that remind me of the graffiti about the exploding mine: I either shut up or I cease to exist in cyberspace.

Finally, as I write these words, I am unable to express myself freely about the two sides of the “battle”. I fear that many have surrendered to the fact that there is no voice above that voice, and I worry that I may be among them.

Biographies

Abbad Yahya is a Palestinian writer. His novel A Crime in Ramallah from which Index published an extract in 2018 was banned by the Palestinian National Authority